Monday, 03 January 2022

11:35 PM

Paul Wise: FLOSS Activities December 2021 [Planet Debian] 11:35 PM, Monday, 03 January 2022 12:40 AM, Tuesday, 04 January 2022

Focus

This month I didn't have any particular focus. I just worked on issues in my info bubble.

Changes

- plac: release cleanup

- bibliogram-docs: update a feed checkbox

- duck: add indicator phrases (1 2 3)

- Debian Planets: remove BlackWeb

- Debian package uploads: purple-discord, python-plac, sptag (1 2 3), mpv-mpris, typer

- Debian wiki pages: AndriusMerkys/PackagingInSeconds, Derivatives/Census/BlackWeb, EmbeddedCopies, Hardening/Goals, InstallingDebianOn, InstallingDebianOn/RaspberryPi, WordPress

- FOSSjobs wiki pages: Resources

- Wikipedia: Personal_Storage_Table

Issues

- Crashes in evince, evolution

- Broken links in oci-python-sdk

- Test failures in smart-open

- Features in Debian package tracker, Debian security tracker, Debian code search, diffoscope

- Binary removal needed for sptag

- Conffile removal needed in privoxy, rpmlint

- Debian package intended for mpv-mpris

- Warnings in tnftp

- Git repo anomalies in plac

- Syntax errors in ceres-solver

- Security issues in a cloud vendor SDK (sent privately)

Review

- Spam: reported 166 Debian mailing list posts

- Patches: reviewed libpst upstream patches

- Debian packages: sponsored nsis, memtest86+

- Debian wiki: RecentChanges for the month

- Debian BTS usertags: changes for the month

- Debian screenshots:

- approved changeme cyclograph-gtk3 fnt fontforge fonts-libfinal gimp imgp

- rejected freecell-solver-bin (not a graphical program), aptitude/chromium-browser (screenshot of screenshots site in mobile browser)

Administration

- libpst: setup GitHub presence, migrate from hg to git, requested details from bug reporters

- plac: cleaned up git repo anomalies

- Debian BTS: unarchive/reopen/triage bugs for reintroduced packages: stardict, node-carto

- Debian wiki: unblock IP addresses, approve accounts

Communication

- Respond to queries from Debian users and contributors on the mailing lists and IRC

Sponsors

The purple-discord, python-plac, sptag, smart-open, libpst, memtest86+, oci-python-sdk work was sponsored. All other work was done on a volunteer basis.

06:35 PM

Ian Jackson: Debian’s approach to Rust - Dependency handling [Planet Debian] 06:35 PM, Monday, 03 January 2022 07:20 PM, Monday, 03 January 2022

tl;dr: Faithfully following upstream semver, in Debian package dependencies, is a bad idea.

Introduction

I have been involved in Debian for a very long time. And I’ve been working with Rust for a few years now. Late last year I had cause to try to work on Rust things within Debian.

When I did, I found it very difficult. The Debian Rust Team were very helpful. However, the workflow and tooling require very large amounts of manual clerical work - work which it is almost impossible to do correctly since the information required does not exist. I had wanted to package a fairly straightforward program I had written in Rust, partly as a learning exercise. But, unfortunately, after I got stuck in, it looked to me like the effort would be wildly greater than I was prepared for, so I gave up.

Since then I’ve been thinking about what I learned about how Rust is packaged in Debian. I think I can see how to fix some of the problems. Although I don’t want to go charging in and try to tell everyone how to do things, I felt I ought at least to write up my ideas. Hence this blog post, which may become the first of a series.

This post is going to be about semver handling. I see problems with other aspects of dependency handling and source code management and traceability as well, and of course if my ideas find favour in principle, there are a lot of details that need to be worked out, including some kind of transition plan.

How Debian packages Rust, and build vs runtime dependencies

Today I will be discussing almost entirely build-dependencies; Rust doesn’t (yet?) support dynamic linking, so built Rust binaries don’t have Rusty dependencies.

However, things are a bit confusing because even the Debian “binary” packages for Rust libraries contain pure source code. So for a Rust library package, “building” the Debian binary package from the Debian source package does not involve running the Rust compiler; it’s just file-copying and format conversion. The library’s Rust dependencies do not need to be installed on the “build” machine for this.

So I’m mostly going to be talking about

Depends fields, which are Debian’s way of

talking about runtime dependencies, even though they are

used only at build-time. The way this works is that some ultimate

leaf package (which is supposed to produce actual executable code)

Build-Depends on the libraries it needs, and those

Depends on their under-libraries, so that everything

needed is installed.

What do dependencies mean and what are they for anyway?

In systems where packages declare dependencies on other packages, it generally becomes necessary to support “versioned” dependencies. In all but the most simple systems, this involves an ordering (or similar) on version numbers and a way for a package A to specify that it depends on certain versions of B.

Both Debian and Rust have this. Rust upstream crates have version numbers and can specify their dependencies according to semver. Debian’s dependency system can represent that.

So it was natural for the designers of the scheme for packaging Rust code in Debian to simply translate the Rust version dependencies to Debian ones. However, while the two dependency schemes seem equivalent in the abstract, their concrete real-world semantics are totally different.

These different package management systems have different practices and different meanings for dependencies. (Interestingly, the Python world also has debates about the meaning and proper use of dependency versions.)

The epistemological problem

Consider some package A which is known to depend on B. In general, it is not trivial to know which versions of B will be satisfactory. I.e., whether a new B, with potentially-breaking changes, will actually break A.

Sometimes tooling can be used which calculates this (eg, the

Debian

shlibdeps system for runtime dependencies) but

this is unusual - especially for build-time dependencies. Which

versions of B are OK can normally only be discovered by a human

consideration of changelogs etc., or by having a computer try

particular combinations.

Few ecosystems with dependencies, in the Free Software community at least, make an attempt to precisely calculate the versions of B that are actually required to build some A. So it turns out that there are three cases for a particular combination of A and B: it is believed to work; it is known not to work; and: it is not known whether it will work.

And, I am not aware of any dependency system that has an explicit machine-readable representation for the “unknown” state, so that they can say something like “A is known to depend on B; versions of B before v1 are known to break; version v2 is known to work”. (Sometimes statements like that can be found in human-readable docs.)

That leaves two possibilities for the semantics of a dependency A depends B, version(s) V..W: Precise: A will definitely work if B matches V..W, and Optimistic: We have no reason to think B breaks with any of V..W.

At first sight the latter does not seem useful, since how would the package manager find a working combination? Taking Debian as an example, which uses optimistic version dependencies, the answer is as follows: The primary information about what package versions to use is not only the dependencies, but mostly in which Debian release is being targeted. (Other systems using optimistic version dependencies could use the date of the build, i.e. use only packages that are “current”.)

| Precise |

Optimistic |

|

|---|---|---|

|

People involved in version management |

Package developers, downstream developers/users. |

Package developers, |

|

Package developers declare versions V and dependency ranges V..W so that |

It definitely works. |

A wide range of B can satisfy the declared requirement. |

|

The principal version data used by the package manager |

Only dependency versions. |

Contextual, eg, Releases - set(s) of packages available. |

|

Version dependencies are for |

Selecting working combinations (out of all that ever existed). |

Sequencing (ordering) of updates; QA. |

|

Expected use pattern by a downstream |

Downstream can combine any declared-good combination. |

Use a particular release of the whole system. Mixing-and-matching requires additional QA and remedial work. |

|

Downstreams are protected from breakage by |

Pessimistically updating versions and dependencies whenever anything might go wrong. |

Whole-release QA. |

|

A substantial deployment will typically contain |

Multiple versions of many packages. |

A single version of each package, except where there are actual incompatibilities which are too hard to fix. |

|

Package updates are driven by |

Top-down: Depending package updates the declared metadata. |

Bottom-up: Depended-on package is updated in the repository for the work-in-progress release. |

So, while Rust and Debian have systems that look superficially similar, they contain fundamentally different kinds of information. Simply representing the Rust versions directly into Debian doesn’t work.

What is currently done by the Debian Rust Team is to manually patch the dependency specifications, to relax them. This is very labour-intensive, and there is little automation supporting either decisionmaking or actually applying the resulting changes.

What to do

Desired end goal

To update a Rust package in Debian, that many things depend on, one need simply update that package.

Debian’s sophisticated build and CI infrastructure will try building all the reverse-dependencies against the new version. Packages that actually fail against the new dependency are flagged as suffering from release-critical problems.

Debian Rust developers then update those other packages too. If the problems turn out to be too difficult, it is possible to roll back.

If a problem with a depending packages is not resolved in a timely fashion, priority is given to updating core packages, and the depending package falls by the wayside (since it is empirically unmaintainable, given available effort).

There is no routine manual patching of dependency metadata (or of anything else).

Radical proposal

Debian should not precisely follow upstream Rust semver dependency information. Instead, Debian should optimistically try the combinations of packages that we want to have. The resulting breakages will be discovered by automated QA; they will have to be fixed by manual intervention of some kind, but usually, simply updating the depending package will be sufficient.

This no longer ensures (unlike the upstream Rust scheme) that the result is expected to build and work if the dependencies are satisfied. But as discussed, we don’t really need that property in Debian. More important is the new property we gain: that we are able to mix and match versions that we find work in practice, without a great deal of manual effort.

Or to put it another way, in Debian we should do as a Rust upstream maintainer does when they do the regular “update dependencies for new semvers” task: we should update everything, see what breaks, and fix those.

(In theory a Rust upstream package maintainer is supposed to do some additional checks or something. But the practices are not standardised and any checks one does almost never reveal anything untoward, so in practice I think many Rust upstreams just update and see what happens. The Rust upstream community has other mechanisms - often, reactive ones - to deal with any problems. Debian should subscribe to those same information sources, eg RustSec.)

Nobbling cargo

Somehow, when cargo is run to build Rust things against these Debian packages, cargo’s dependency system will have to be overridden so that the version of the package that is actually selected by Debian’s package manager is used by cargo without complaint.

We probably don’t want to change the Rust version numbers

of Debian Rust library packages, so this should be done by either

presenting cargo with an automatically-massaged

Cargo.toml where the dependency version restrictions

are relaxed, or by using a modified version of cargo which has

special option(s) to relax certain dependencies.

Handling breakage

Rust packages in Debian should already be provided with autopkgtests so that ci.debian.net will detect build breakages. Build breakages will stop the updated dependency from migrating to the work-in-progress release, Debian testing.

To resolve this, and allow forward progress, we will usually

upload a new version of the dependency containing an appropriate

Breaks, and either file an RC bug against the

depending package, or update it. This can be done after the upload

of the base package.

Thus, resolution of breakage due to incompatibilities will be done collaboratively within the Debian archive, rather than ad-hoc locally. And it can be done without blocking.

My proposal prioritises the ability to make progress in the core, over stability and in particular over retaining leaf packages. This is not Debian’s usual approach but given the Rust ecosystem’s practical attitudes to API design, versioning, etc., I think the instability will be manageable. In practice fixing leaf packages is not usually really that hard, but it’s still work and the question is what happens if the work doesn’t get done. After all we are always a shortage of effort - and we probably still will be, even if we get rid of the makework clerical work of patching dependency versions everywhere (so that usually no work is needed on depending packages).

Exceptions to the one-version rule

There will have to be some packages that we need to keep multiple versions of. We won’t want to update every depending package manually when this happens. Instead, we’ll probably want to set a version number split: rdepends which want version <X will get the old one.

Details - a sketch

I’m going to sketch out some of the details of a scheme I think would work. But I haven’t thought this through fully. This is still mostly at the handwaving stage. If my ideas find favour, we’ll have to do some detailed review and consider a whole bunch of edge cases I’m glossing over.

The dependency specification consists of two halves: the

depending .deb‘s Depends (or, for a

leaf package, Build-Depends) and the base

.deb’ Version and perhaps

Breaks and

Provides.

Even though libraries vastly outnumber leaf packages, we still want to avoid updating leaf Debian source packages simply to bump dependencies.

Dependency encoding proposal

Compared to the existing scheme, I suggest we implement the dependency relaxation by changing the depended-on package, rather than the depending one.

So we retain roughly the existing semver translation for

Depends fields. But we drop all local patching of

dependency versions.

Into every library source package we insert a new

Debian-specific metadata file declaring the earliest version that

we uploaded. When we translate a library source package to a

.deb, the “binary” package build adds

Provides for every previous version.

The effect is that when one updates a base package, the usual behaviour is to simply try to use it to satisfy everything that depends on that base package. The Debian CI will report the build or test failures of all the depending packages which the API changes broke.

We will have a choice, then:

Breakage handling - update broken depending packages individually

If there are only a few packages that are broken, for each

broken dependency, we add an appropriate Breaks to the

base binary package. (The version field in the Breaks

should be chosen narrowly, so that it is possible to resolve it

without changing the major version of the dependency, eg by making

a minor source change.)

When can then do one of the following:

-

Update the dependency from upstream, to a version which works with the new base. (Assuming there is one.) This should be the usual response.

-

Fix the dependency source code so that builds and works with the new base package. If this wasn’t just a backport of an upstream change, we should send our fix upstream. (We should prefer to update the whole package, than to backport an API adjustment.)

-

File an RC bug against the dependency (which will eventually trigger autoremoval), or preemptively ask for the Debian release managers to remove the dependency from the work-in-progress release.

Breakage handling - declare new incompatible API in Debian

If the API changes are widespread and many dependencies are

affected, we should represent this by changing the

in-Debian-source-package metadata to arrange for fewer

Provides lines to be generated - withdrawing the

Provides lines for earlier APIs.

Hopefully examination of the upstream changelog will show what

the main compat break is, and therefore tell us which

Provides we still want to retain.

This is like declaring Breaks for all the

rdepends. We should do it if many rdepends are affected.

Then, for each rdependency, we must choose one of the responses in the bullet points above. In practice this will often be a mass bug filing campaign, or large update campaign.

Breakage handling - multiple versions

Sometimes there will be a big API rewrite in some package, and we can’t easily update all of the rdependencies because the upstream ecosystem is fragmented and the work involved in reconciling it all is too substantial.

When this happens we will bite the bullet and include multiple versions of the base package in Debian. The old version will become a new source package with a version number in its name.

This is analogous to how key C/C++ libraries are handled.

Downsides of this scheme

The first obvious downside is that assembling some arbitrary set of Debian Rust library packages, that satisfy the dependencies declared by Debian, is no longer necessarily going to work. The combinations that Debian has tested - Debian releases - will work, though. And at least, any breakage will affect only people building Rust code using Debian-supplied libraries.

Another less obvious problem is that because there is no such

thing as Build-Breaks (in a Debian binary package),

the per-package update scheme may result in no way to declare that

a particular library update breaks the build of a particular leaf

package. In other words, old source packages might no longer build

when exposed to newer versions of their build-dependencies, taken

from a newer Debian release. This is a thing that already happens

in Debian, with source packages in other languages, though.

Semver violation

I am proposing that Debian should routinely compile Rust packages against dependencies in violation of the declared semver, and ship the results to Debian’s millions of users.

This sounds quite alarming! But I think it will not in fact lead to shipping bad binaries, for the following reasons:

The Rust community strongly values safety (in a broad sense) in its APIs. An API which is merely capable of insecure (or other seriously bad) use is generally considered to be wrong. For example, such situations are regarded as vulnerabilities by the RustSec project, even if there is no suggestion that any actually-broken caller source code exists, let alone that actually-broken compiled code is likely.

The Rust community also values alerting programmers to problems. Nontrivial semantic changes to APIs are typically accompanied not merely by a semver bump, but also by changes to names or types, precisely to ensure that broken combinations of code do not compile.

Or to look at it another way, in Debian we would simply be doing what many Rust upstream developers routinely do: bump the versions of their dependencies, and throw it at the wall and hope it sticks. We can mitigate the risks the same way a Rust upstream maintainer would: when updating a package we should of course review the upstream changelog for any gotchas. We should look at RustSec and other upstream ecosystem tracking and authorship information.

Difficulties for another day

As I said, I see some other issues with Rust in Debian.

-

I think the library “feature flag” encoding scheme is unnecessary. I hope to explain this in a future essay.

-

I found Debian’s approach to handling the source code for its Rust packages quite awkward; and, it has some troubling properties. Again, I hope to write about this later.

-

I get the impression that updating rustc in Debian is a very difficult process. I haven’t worked on this myself and I don’t feel qualified to have opinions about it. I hope others are thinking about how to make things easier.

Thanks all for your attention!

12:23 PM

Thorsten Alteholz: My Debian Activities in December 2021 [Planet Debian] 12:23 PM, Monday, 03 January 2022 12:40 PM, Monday, 03 January 2022

FTP master

This month I accepted 412 and rejected 44 packages. The overall number of packages that got accepted was 423.

Debian LTS

This was my ninetieth month that I did some work for the Debian LTS initiative, started by Raphael Hertzog at Freexian.

This month my all in all workload has been 40h. During that time I did LTS and normal security uploads of:

- [DLA 2846-1] raptor2 security update for one CVE

- [DLA 2845-1] libsamplerate security update for one CVE

- [DLA 2859-1] zziplib security update for one CVE

- [DLA 2858-1] libzip security update for one CVE

- [DLA 2869-1] xorg-server security update for three CVEs

- [#1002912] for graphicsmagick in Buster

- [debdiff] for sphinxearch/buster to maintainer and sec team

- [debdiff] for zziplib/buster to maintainer

- [debdiff] for zziplib/bullseye to maintainer

- [debdiff] for raptor2/bullseye to maintainer

I also started to work on libarchive

Further I worked on packages in NEW on security-master. In order to faster process such packages, I added a notification when work arrived there.

Last but not least I did some days of frontdesk duties.

Debian ELTS

This month was the forty-second ELTS month.

During my allocated time I uploaded:

- ELA-527-1 for libsamplerate

- ELA-528-1 for raptor2

- ELA-529-1 for ufraw

- ELA-532-1 for zziplib

- ELA-534-1 for xorg-server

Last but not least I did some days of frontdesk duties.

Debian Astro

Related to my previous article about fun with telescopes I uploaded new versions or did source uploads for:

- … indi-aagcloudwatcher-ng

- … indi-aok

- … indi-apogee

- … indi-armadillo-platypus

- … indi-asi

- … indi-astrolink4

- … indi-astromechfoc

- … indi-avalon

- … indi-beefocus

- … indi-bresserexos2

- … indi-dreamfocuser

- … indi-dsi

- … indi-eqmod

- … indi-ffmv

- … indi-fishcamp

- … indi-fli

- … indi-gige

- … indi-gphoto

- … indi-gpsd

- … indi-gpsnmea

- … indi-inovaplx

- … indi-limesdr

- … indi-maxdomeii

- … indi-mgen

- … indi-nexdome

- … indi-nightscape

- … indi-orion-ssg3

- … indi-pentax

- … indi-rtklib

- … indi-sbig

- … indi-shelyak

- … indi-spectracyber

- … indi-starbook

- … indi-starbook-ten

- … indi-sx

- … indi-talon6

- … indi-webcam

- … libapogee3

- … libasi

- … libfishcamp

- … libfli

- … libinovasdk

- … libpktriggercord

- … libricohcamerasdk

- … libsbig

Besides the indi-stuff I also uploaded

Other stuff

I celebrated christmas :-).

10:20 AM

Joachim Breitner: Telegram bots in Python made easy [Planet Debian] 10:20 AM, Monday, 03 January 2022 11:20 AM, Monday, 03 January 2022

A while ago I set out to get some teenagers interested in programming, and thought about a good way to achieve that. A way that allows them to get started with very little friction, build something that’s relevant in their currently live quickly, and avoids frustration.

They were old enough to have their own smartphone, and they were

already happily chatting with their friends, using the Telegram messenger. I have already

experimented a bit with writing bots for Telegram

(e.g. @Umklappbot or @Kaleidogen), and it

occurred to me that this might be a good starting point: Chat bot

interactions have a very simple data model: message in, response

out, all simple text. Much simpler than anything graphical or even

web programming. In a way it combines the simplicity of the typical

initial programming exercises on the command-line with the impact

and relevance of web programming.

But of course “real” bot programming is still too hard – installing a programming environment, setting up a server, deploying, dealing with access tokens, understanding the Telegram Bot API and mapping it to your programming language.

The

IDE

The

IDESo I built a browser-based Python programming environments for Telegram bots that takes care of all of that. You simply write a single Python function, click the “Deploy” button, and the bot is live. That’s it!

This environment provides a much simpler “API” for the bots: Define a function like the following:

def private_message(sender, text):

return "Hello!"This gets called upon a message, and if it returns a

String, that’s the response. That’s it!

Not enough to build any kind of Telegram bot, but sufficient for

many fun applications.

A

chatbot

A

chatbotIn fact, my nephew and niece use this to build a simple interactive fiction game, where the player says where they are going (“house”, ”forest”, “lake”) and thus explore the story, and in the end kill the dragon. And my girlfriend created a shopping list bot that we are using “productively”.

If you are curious, you can follow the instructions to create your own bot. There you can also find the source code and instructions for hosting your own instance (on Amazon Web Services).

Help with the project (e.g. improving the sandbox for running untrustworthy python code; making the front-end work better) is of course highly appreciated, too. The frontend is written in PureScript, and the backend in Python, building on Amazon lambda and Amazon DynamoDB.

08:52 AM

Birger Schacht: Introducing carl [Planet Debian] 08:52 AM, Monday, 03 January 2022 06:00 PM, Monday, 03 January 2022

For some time now I wanted to learn Rust, but I either didn’t have the time or couldn’t come up with a nice beginner project. Given that I recently found myself to be without a job and we had another lockdown in the part of the world I happen to live in, I decided to give that idea another go (no pun intended).

There is apparently a trend to reimplement existing Unix tools

in Rust (see exa, a

‘modern replacement for ls’, delta, a syntax

highlighting pager for git, diff and grep output, bat, a ‘cat clone with

wings’, zellij, a terminal

workspace, ripgrep, a

line-oriented search tool …). I looked around what else was

out there, but what I wasn’t able to find was an

implementation of cal(1) in Rust (maybe I wasn’t

looking hard enough, feel free to point anything out to me I might

have overlooked). No cal in Rust even though a

calendar implementation would provide the potential to go over the

top with terminal colors, which is also very important when writing

reimplementations of older CLI tools! So I started writing and soon

had a simple prototype of a cal reimplementation. A

couple of weeks later I can now present carl, a

cal implementation in Rust:

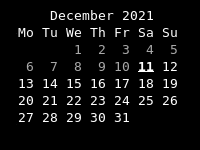

The default output of carl is what you would expect

from a commandline calendar tool. It prints the days of the current

month and highlights the current day. Other than the

cal tools I tried, carl by default also

prints days that are in the past in grey. Like cal it

can also print three month if you use the -3 switch or

the whole year if you use the -y switch.

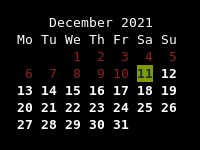

Colors

You can use a theme file to change the colors carl

uses for various dates. The name of the theme is set in

carls configuration file (in

XDG_CONFIG_HOME/.carl/config.toml or system-wide in

XDG_CONFIG_DIRS/.carl/config.toml) using the

theme setting - carl looks for the theme in the file

${themename}.theme in the configuration folders. A

custom theme could for example look like this:

You can change the foreground color, background color and/or

style of a date using a combination of various stylenames like

BGRed, Bold and FGCyan. The

README

lists all possible stylenames. A list of date properties

defines which dates the specific style should affect- date

properties are for example CurrentDate,

AfterCurrentDate or FirstDayOfMonth.

Again, the README

lists the existing date properties and I’m happy to implement

more of them, if you have ideas.

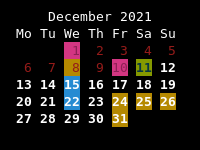

Ical support

I also added the option to list .ical files in the

configuration file. carl can display the dates from

the ical file(s) with a separate style. There can either be a

global style for all the dates from all the ical files by using the

IsEvent date property or a separate style for the

dates of a specific *.ical file.

Using the --agenda commandline switch

carl also shows an agenda of dates from the

ical files.

Installation

I have uploaded carl to

crates.io, so you can install carl using cargo: cargo

install carl. I also plan to upload it to Debian at some

point. If you find bugs or have feature requests, please

don’t hesitate to create issues.