Monday, 06 January 2020

02:00 PM

The 'Spelling Bee Honeycomb' puzzle: efficient computation in R [Variance Explained] 02:00 PM, Monday, 06 January 2020 01:20 AM, Tuesday, 24 November 2020

Previously in this series:

- The “lost boarding pass” puzzle

- The “deadly board game” puzzle

- The “knight on an infinite chessboard” puzzle

- The “largest stock profit or loss” puzzle

- The “birthday paradox” puzzle

I love 538’s Riddler column, and the January 3 puzzle is a fun one. I’ll quote:

The New York Times recently launched some new word puzzles, one of which is Spelling Bee. In this game, seven letters are arranged in a honeycomb lattice, with one letter in the center. Here’s the lattice from December 24, 2019:

The goal is to identify as many words that meet the following criteria:

- The word must be at least four letters long.

- The word must include the central letter.

- The word cannot include any letter beyond the seven given letters.

Note that letters can be repeated. For example, the words GAME and AMALGAM are both acceptable words. Four-letter words are worth 1 point each, while five-letter words are worth 5 points, six-letter words are worth 6 points, seven-letter words are worth 7 points, etc. Words that use all of the seven letters in the honeycomb are known as “pangrams” and earn 7 bonus points (in addition to the points for the length of the word). So in the above example, MEGAPLEX is worth 15 points.

Which seven-letter honeycomb results in the highest possible game score? To be a valid choice of seven letters, no letter can be repeated, it must not contain the letter S (that would be too easy) and there must be at least one pangram.

Solving this puzzle in R is interesting enough, but it’s particularly challenging to do so in a computationally efficient way. As much as I love the tidyverse, this, like the “lost boarding pass” puzzle and Emily Robinson’s evaluation of the best Pokémon team, serves as a great example of using R’s matrix operations to work efficiently with data.

I’ve done a lot of puzzles recently, and I realized that showing the end result isn’t a representation of my thought process. I don’t show all the dead ends and bugs, or explain why I ended up choosing a particular path. So in the same spirit as my Tidy Tuesday screencasts, I recorded myself solving this puzzle (though not the process of turning it into a blog post).

Setup: Processing the word list

Our first step is to process the word list for words that could appear in a honeycomb puzzle. Based on the above rules, these will have at least four letters, have no more than 7 unique letters, and never contain the letter S. We’ll do this processing with tidyverse functions.

library(tidyverse)

words <- tibble(word = read_lines("https://norvig.com/ngrams/enable1.txt")) %>%

mutate(word_length = str_length(word)) %>%

filter(word_length >= 4,

!str_detect(word, "s")) %>%

mutate(letters = str_split(word, ""),

letters = map(letters, unique),

unique_letters = lengths(letters)) %>%

mutate(points = ifelse(word_length == 4, 1, word_length) +

7 * (unique_letters == 7)) %>%

filter(unique_letters <= 7) %>%

arrange(desc(points))

words## # A tibble: 44,585 x 5

## word word_length letters unique_letters points

## <chr> <int> <list> <int> <dbl>

## 1 antitotalitarian 16 <chr [7]> 7 23

## 2 anticlimactical 15 <chr [7]> 7 22

## 3 inconveniencing 15 <chr [7]> 7 22

## 4 interconnection 15 <chr [7]> 7 22

## 5 micrometeoritic 15 <chr [7]> 7 22

## 6 nationalization 15 <chr [7]> 7 22

## 7 nonindependence 15 <chr [7]> 7 22

## 8 nonintervention 15 <chr [7]> 7 22

## 9 nontotalitarian 15 <chr [7]> 7 22

## 10 overengineering 15 <chr [7]> 7 22

## # … with 44,575 more rowsThere are 44585 that are eligible to appear in a puzzle. This data gives us a way to solve the December 24th Honeycomb puzzle that comes with the Riddler column.

get_words <- function(center_letter, other_letters) {

all_letters <- c(center_letter, other_letters)

words %>%

filter(str_detect(word, center_letter)) %>%

mutate(invalid_letters = map(letters, setdiff, all_letters)) %>%

filter(lengths(invalid_letters) == 0) %>%

select(word, points)

}

honeycomb_words <- get_words("g", c("a", "p", "x", "m", "e", "l"))

honeycomb_words## # A tibble: 43 x 2

## word points

## <chr> <dbl>

## 1 amalgam 7

## 2 agapae 6

## 3 agleam 6

## 4 allege 6

## 5 gaggle 6

## 6 galeae 6

## 7 gemmae 6

## 8 pelage 6

## 9 plagal 6

## 10 agama 5

## # … with 33 more rowssum(honeycomb_words$points)## [1] 153Looks like the score is 153.

Could we use this get_words() function

to brute force every possible honeycomb? Only if we had a lot of

time on our hands. Since S is eliminated, there are 25 possible

choices for the center letter, and \(24\choose 6\) (“24

choose 6”) possible combinations of outer letters, making

25 * choose(24,

6) = 3.36 million possible honeycombs. It

would take about 8 days to test every one this way. We can do a lot

better.

Heuristics: What letters appear in the highest-scoring words?

Would you expect the winning honeycomb to have letters like X, Z, or Q? Neither would I. The winning honeycomb is likely filled with common letters like E that appear in lots of words.

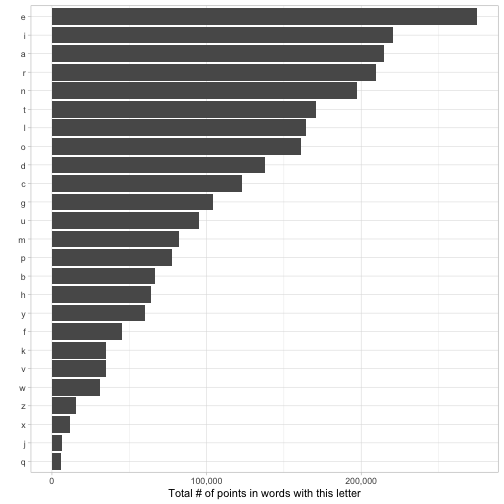

Let’s quantify this, by looking at how many words each letter appears in, and how many total points they’d earn.

library(tidytext)

# unnest_tokens is a fast approach to splitting one-character-per-row

letters_unnested <- words %>%

select(word, points) %>%

unnest_tokens(letter, word, token = "characters", drop = FALSE) %>%

distinct(word, letter, .keep_all = TRUE)

letters_summarized <- letters_unnested %>%

group_by(letter) %>%

summarize(n_words = n(),

n_points = sum(points)) %>%

arrange(desc(n_points))

letters_summarized## # A tibble: 25 x 3

## letter n_words n_points

## <chr> <int> <dbl>

## 1 e 28203 275039

## 2 i 21128 220473

## 3 a 21719 214490

## 4 r 20977 209803

## 5 n 18735 197485

## 6 t 16232 170953

## 7 l 16503 164552

## 8 o 16038 160863

## 9 d 13894 137491

## 10 c 11644 123224

## # … with 15 more rowsWhat letters have the most and least points?

Of course, any given honeycomb with one of these letters will get only a tiny fraction of the points available to the letter. There could be interactions between those terms (maybe two relatively rare letters go well together). But it gives us a sense of which letters are likely to be included (almost certainly not ones like X, Z, Q, and J), which may help us narrow down our search space in the next step.

Using matrices to score honeycombs

When you need R to be very efficient, you might want to turn to matrix operations, which when used properly are some of the fastest operations in R. Luckily, it turns out that a lot of this puzzle can be done through linear algebra. I’m presenting this as the finished product, but if you’re interested in my thought process as I came up with it I do recommend running through the screencast recording to show how I got here.

We start by creating a word-by-letter matrix.

There are 44K words and (without S) 25 letters. To operate

efficiently on these, we’ll want these in a 44K x 25 binary

matrix rather than strings. The underrated reshape2::acast can

set this up for us.

word_matrix <- letters_unnested %>%

reshape2::acast(word ~ letter, fun.aggregate = length)

dim(word_matrix)## [1] 44585 25head(word_matrix)## a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r t u v w x y z

## aahed 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

## aahing 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

## aalii 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

## aardvark 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0

## aardwolf 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0

## aargh 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0A points-per-word vector. Once we have the set of words that are possible with each honeycomb, we’ll need to score them to find the maximum.

points_per_word <- setNames(words$points, words$word)

head(points_per_word)## antitotalitarian anticlimactical inconveniencing interconnection

## 23 22 22 22

## micrometeoritic nationalization

## 22 22At this point, we take a matrix multiplication approach to score all the honeycomb combinations. Since I went through it in the screencast, I won’t walk through each of the steps except in the comments.

find_best_score <- function(center_letter, possible_letters) {

# Find all 6-letter combinations for the outside letters

outside <- setdiff(possible_letters, center_letter)

combos <- combn(outside, 6)

# Binary matrix with one row per combination, 1 means letter is forbidden

forbidden_matrix <- 1 - apply(combos, 2, function(.) {

colnames(word_matrix) %in% c(center_letter, .)

})

# Must contain the center letter, can't contain any forbidden

filtered_word_matrix <- word_matrix[word_matrix[, center_letter] == 1, ]

allowed_matrix <- (filtered_word_matrix %*% forbidden_matrix) == 0

# Score all the words, and add them up within each combination

scores <- t(allowed_matrix) %*% points_per_word[rownames(allowed_matrix)]

# Find the highest score, and return a tibble with all useful info

tibble(center_letter = center_letter,

other_letters = paste(combos[, which.max(scores)], collapse = ","),

score = max(scores))

}In this approach, I hold the center letter constant, and try

every combination of 6 within a pool of letters (the possible_letters

argument) for the outer letters.

If we use all 25 available letters, this ends up impractically slow and memory-intensive (we end up with something like a 40,000 by 135,000 matrix). But if we bring it down to 15 letters, it can run in a few seconds per central letter. Here I’ll use the heuristic we came up with above: it’s likely that the winning solution is made up of mostly the ones that appear in lots of high-scoring words, like E, I, and A.

pool <- head(letters_summarized$letter, 15)

# Try each as a center letter, along with the pool

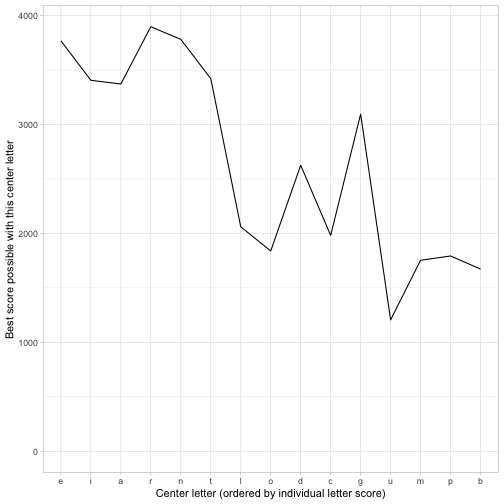

best_scores <- purrr::map_df(pool, find_best_score, pool)best_scores## # A tibble: 15 x 3

## center_letter other_letters score

## <chr> <chr> <dbl>

## 1 e i,a,r,n,t,g 3769

## 2 i e,a,r,n,t,g 3406

## 3 a e,i,r,n,t,g 3372

## 4 r e,i,a,n,t,g 3898

## 5 n e,i,a,r,t,g 3782

## 6 t e,i,a,r,n,g 3421

## 7 l e,i,a,n,t,g 2061

## 8 o e,i,r,n,t,c 1839

## 9 d e,i,a,r,n,g 2626

## 10 c e,i,a,r,n,t 1982

## 11 g e,i,a,r,n,t 3095

## 12 u e,a,r,n,t,d 1206

## 13 m e,i,a,r,n,t 1754

## 14 p e,a,r,t,l,d 1793

## 15 b e,i,a,r,l,d 1673It takes about a minute to try all combinations of the top 15 letters. This makes it clear: the best combination is R in the center, and E, I, A, N, T, G surrounding it, for a total score of 3898.

How good was our heuristic at judging letters?

We took a shortcut, and therefore a bit of risk, in winnowing down the alphabet to just 15 letters. How could we get a sense of whether we still got the right answer?

We could start by looking at how good a predictor our heuristic was of how good a letter is in the center.

best_scores %>%

mutate(center_letter = fct_inorder(center_letter)) %>%

ggplot(aes(center_letter, score)) +

geom_line(group = 1) +

expand_limits(y = 0) +

labs(x = "Center letter (ordered by individual letter score)",

y = "Best score possible with this center letter")

We can see that the heuristic isn’t perfect. For instance, G is a surprisingly good center letter (and makes it into the outer letters of our winning honeycomb) considering that overall it doesn’t quite make the top 10 for our heuristic. However, it’s unlikely we’re missing anything with the rarer letters.

Offline, I tried running this code with the top 21 letters (that is, all but Z, X, J, and Q) and while it takes a long time to run it confirms that you can’t beat R/EIRNTG, and that none of the letters after G are particularly strong.

Shortcut: Pangrams

It wasn’t until later in the day (2020-01-06) that I posted this that Hector Pefo pointed out an excellent shortcut.

You can find all possible 7-letter sets that yield pangrams (only about 8K), generate word-lists for these sets, and then score all 56K possible bees. 23sec. Same answer, but nowhere near as interesting a process! https://t.co/ue6AXqqk9s

— Hector Pefo (@HectorPefo) January 6, 2020

I’d ignored the “each puzzle must have a pangram” rule (since I confirmed that whatever won haed at least one), but I hadn’t thought of using it as a shortcut. Thanks to this approach, we can do this a good deal faster, and without relying on heuristics!

We’d start by making a binary matrix of the legal pangrams.

possible_pangrams <- words %>%

filter(unique_letters == 7) %>%

mutate(letters = map_chr(letters, ~ paste(sort(.), collapse = ","))) %>%

distinct(letters) %>%

mutate(combination = letters) %>%

separate_rows(letters) %>%

reshape2::acast(combination ~ letters, fun.aggregate = length)

head(possible_pangrams)## a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r t u v w x y z

## a,b,c,d,e,f,k 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

## a,b,c,d,e,f,r 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

## a,b,c,d,e,h,l 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

## a,b,c,d,e,h,n 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

## a,b,c,d,e,h,o 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

## a,b,c,d,e,h,r 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0There are only 7986 combinations of seven letters that offer a pangram, meaning there are 7 x 7986 = 5.5902 × 104 possible.

We can modify the matrix multiplication to score each of these

combinations. As part of this process, I’ve also figured out

how to test all the central letters in one additional matrix

multiplication (which I could have done in the original solution if

we’d used the word_by_center

matrix).

library(Matrix)

# This is efficient only with sparse matrices

word_matrix_sparse <- as(word_matrix, "sparseMatrix")

# Find the words that are possible with each pangram

pangram_words <- word_matrix_sparse %*% t(1 - possible_pangrams) == 0

# Find the matrix of word scores based on what the center letter is

# A word is included only if it has that central letter

word_by_center <- points_per_word[rownames(word_matrix)] * word_matrix_sparse

# Create a 8K by 25 matrix: best combination + best center letter

scores <- t(pangram_words) %*% word_by_center

# Tidy the matrix

puzzle_solutions <- reshape2::melt(as.matrix(scores),

varnames = c("combination", "center"),

value.name = "score") %>%

as_tibble() %>%

filter(score > 0) %>%

arrange(desc(score))

puzzle_solutions## # A tibble: 55,902 x 3

## combination center score

## <fct> <fct> <dbl>

## 1 a,e,g,i,n,r,t r 3898

## 2 a,e,g,i,n,r,t n 3782

## 3 a,e,g,i,n,r,t e 3769

## 4 a,d,e,i,n,r,t e 3672

## 5 a,e,g,i,n,r,t t 3421

## 6 a,e,g,i,n,r,t i 3406

## 7 a,e,g,i,n,r,t a 3372

## 8 a,d,e,g,i,n,r e 3271

## 9 a,d,e,g,i,n,r r 3236

## 10 a,d,e,i,l,r,t e 3194

## # … with 55,892 more rowsWith this scores matrix, we can

confirm our finding of the highest combination, center and score.

It also shows that the top three puzzles all have the same

combination (but different center letters).

This is pretty fast (about 25 seconds for me), and runs without any heuristics. It also lets us discover the worst score!

puzzle_solutions %>%

arrange(score)## # A tibble: 55,902 x 3

## combination center score

## <fct> <fct> <dbl>

## 1 c,i,n,o,p,r,x x 14

## 2 b,i,m,n,r,u,v v 15

## 3 b,e,j,k,o,u,x x 15

## 4 c,f,l,n,o,u,x x 15

## 5 a,c,e,i,q,u,z z 15

## 6 d,f,h,n,o,u,x x 16

## 7 e,i,o,q,t,u,x x 16

## 8 a,b,d,i,j,r,y j 17

## 9 a,c,d,j,q,r,u q 17

## 10 b,h,i,l,p,u,w w 17

## # … with 55,892 more rowsThis reveals that there’s only one combination,

c,i,n,o,p,r,x with

center letter x, that has the

minimum possible Spelling Bee score of 14: a single 7-letter

pangram where the combination offers no other words. (If

you’re interested, the word is “princox”).

Conclusion

After a decade programming in R, I still love the process of journeying through multiple approaches to a problem, and iterating before I find an efficient and elegant solution. An important part of the process was also sharing the work publicly and getting feedback, so that Hector could contribute a deeper optimization. Just because we end up with a handful of matrix multiplications doesn’t mean it’s easy to get there, especially when you’re out of practice with linear algebra like I am.

Every time I practice linear algebra pic.twitter.com/xDgXkFB8xD

— David Robinson (@drob) March 28, 2016

That’s why I’m glad that I recorded and shared my first attempt at this puzzle, including my dead ends and misunderstandings. (I even originally misunderstood the end goal of the puzzle, far from the first time that’s happened!) I hope it’s useful to you too!