Wednesday, 21 July 2021

08:00 PM

Machine learning in a hurry: what I've learned from the SLICED ML competition (local copy) [Variance Explained] 08:00 PM, Wednesday, 21 July 2021 06:40 PM, Friday, 10 September 2021

This summer I’ve been competing in the SLICED machine learning competition, where contestants have two hours to open a new dataset, build a predictive model, and be scored as a Kaggle submission. Contestants are graded primarily on model performance, but also get points for visualization and storytelling, and from audience votes. Before SLICED I had almost no experience with competitive ML, so I learned a lot!

For four of the SLICED episodes (including the two weeks I was competing) I shared a screencast of my process. Episodes 4 and 7 were the ones I was competing live (you can also find the code here):

- Episode 1: Board Game Ratings

- Episode 4: Rain in Australia

- Episode 5: AirBnb Prices

- Episode 7: Credit churn risk

If you watch just one, I recommend AirBnb, which was a blast! (It was easily my favorite dataset of the competition, with a mix of text, geographic, and categorical data- though episode 1 and episode 8 were also delightful).

In this post, I’ll share some of what I’ve learned about using R, and the tidymodels collection of packages, for competitive Kaggle modeling.

The tidymodels packages

For years Python has had a solid advantage in tooling for machine learning (scikit-learn is just dynamite), but R has been catching up fast. The tidyverse team at RStudio has been developing the tidymodels suite of packages to play well with the tidyverse tools. This was the first time I’d really gotten in-depth experience with them, and I’ll share what I liked (and didn’t).

Pit of success

The “pit of success”, in contrast to a “summit of success” or a “pit of doom”, is the philosophy that users shouldn’t have to strive and struggle to do the right thing. They should be able to fall into good habits almost by accident, because it’s easier than using them incorrectly.

There’s a lot of traps you can fall into when doing machine learning, and the tidymodels packages are designed to avoid those “without thinking”. I think the single most impressive one is avoiding data leakage during your data cleaning.

Recipes and data leakage

Think of a few of the many feature engineering steps we might apply to a dataset before fitting a model:

- Imputing missing values (e.g. with mean)

- Dimensionality reduction (e.g. with PCA)

- Bucketing rare categories (e.g. replacing rare levels of a categorical variable with “Other”)

The recipes package offers functions for performing these

operations (like step_impute_mean,

step_pca,

and step_other), but

that’s only part of its value. The brilliant insight of the

recipes packages is that each of those feature engineering

steps is itself a model that needs to be trained! If you

include the test set when you’re imputing values with their

mean, or when you’re applying PCA, you’re accidentally

letting in information from the test set (which makes you more

likely to overfit and not realize it).

The recipes package makes this explicit: a recipe has to be

trained on data (with prep()) before it is

applied to a dataset (with bake()). By combining

this recipe with a model specification into a workflow object, you

encapsulate the entire start-to-end process of feature engineering

and modeling. Other tidymodels tools then take advantage of this

encapsulated workflow.

Other packages

I’ve found each of the other packages also plays a role in the tidymodels “pit of success”. For instance:

- Cross validation (rsamples): Cross validation

is one of the key ways to avoid overfitting, especially when

selecting models and choosing hyperparameters.

vfold_cvandfit_resamplesmake it easy. - Tuning hyperparameters (tune):

tune_gridmakes it trivial to specify a combination of hyperparameters see how the performance varies.autoplot()in particular has a real “does exactly what I want out of the box” feel. - Trying different models (parsnip): I really like not having to deal with each modeling package’s idiosyncrasies of inputs and outputs; less time reading docs means more time focusing on my model and data.

- Text classification (textrecipes): This has a special place in my heart. I helped develop the tidytext package, but I’ve never been completely thrilled with how it fit into a machine learning workflow. By providing tools for tokenization and filtering, the textrecipes package turns text into just another type of predictor.

These conveniences aren’t just a matter of saving effort or time; together they add up to a more robust and effective process. Prior to tidymodels, I might have just skipped tuning a parameter, or stopped with the first model type I tried, because iterating would be too difficult (a phenomenon known as shlep blindness).

Some of the resistance I’ve seen to tidymodels comes from a place of “This makes it too easy- you’re not thinking carefully about what the code is doing!” But I think this is getting it backwards. By removing the burden of writing procedural logic, I get to focus on scientific and statistical questions about my data and model.

Silly complaint: "this tool keeps you from thinking." No one stops thinking when they use good tools. They think about more important things

— David Robinson (@drob) August 26, 2016

Where tidymodels can improve

I wasn’t happy with everything about the tidymodels packages, especially when I first started the competition. In some cases I felt the API forced excessive piping when they could have used function arguments, making the model specifications much more verbose than they had to be. And as I’ll discuss later, the stacks package still feels like a terrific idea with a rough draft implementation.

But the great news is that the team is continuing to improve it! I opened two GitHub issues (parsnip and workflows) in the course of my SLICED competition, and by the time I reached my second lap they were already fixed!1

In tonight's #SLICED, gonna be rocking the development versions of parsnip & workflows

— David Robinson (@drob) July 14, 2021

A. parsnip models now have a default instead of needing set_engine()

B. workflow() now takes a preprocessor / spec argument

💕 the recent work from the tidymodels team https://t.co/2O4Xfen2kU pic.twitter.com/9yI4FYTilu

Gradient boosted trees are incredible, and easy to tune

Now that I’ve talked about the tools, I’ll get to the machine learning itself.

I know I’m just about the last person to appreciate this, but it was remarkable how powerful xgboost was at creating high performance models quickly. When I was practicing for the competition, I honed in on a process early on. Something like:

- Pick out the numeric variables, or the low-cardinality categorical ones

- Mean-impute missing values, if any

- Fit an xgboost boosted trees model, with learn_rate = .02, mtry varying from 2-4, and trees varying from 300 to 800

- Plot a learning curve (showing the performance as the number of trees varies), and use it to adjust mtry and trees if needed.

In most of the episodes, this rote process usually me most of the way to my final model! It almost always outperformed anything I could get from linear or random forest models even with heavy feature engineering and tuning. The process is especially convenient because you can get an entire learning curve (varying the number of trees) from a single model fit, so it’s a very fast use of the tune package.

This is very different from my experience with keras (a deep learning framework), which I found I’d usually have to spend a solid amount of time fiddling with hyperparameters before I could even beat a random forest. It’s certainly possible that keras could have been beaten some of my boosted trees, but I doubt I would have gotten to it nearly as quickly.

In my own professional work I usually like to build interpretable models, make visualizations, and understand the role of each feature. But boosted trees are farther in the direction of “black boxes”. But competitive ML has an amusing way of “focusing the mind” on a performance metric.

Besides which, I was impressed how much I could learn from an importance measure like Gini coefficient. Unlike the features in a linear model, these could represent interesting nonlinear terms, and it helped highlight unimportant terms I could drop from the model. Speaking of which…

Even with xgboost, feature engineering can still help!

Something I quickly discovered with xgboost is that providing too many features could easily hurt it. Low-value features in an xgboost dilute the importance of the remaining ones, since they show up in fewer randomly selected trees. This is in contrast to regularized linear regression (e.g. LASSO), where it’s usually pretty easy for the penalty term to set extra coefficients to zero.

This pops up when we have categorical predictors. If a category has 20 levels, then when turned into one-hot encoding that’s 20 additional binary variables. Those end up in a lot more trees than (say) one or two highly predictive models. I tended to find that my models performed better when I just removed high-cardinality variables up front (my understanding is that catboost might handle these more gracefully!)

Stacking models is even better!

Once you’ve hit a point of diminishing returns when tuning a model, it’s often better to start fresh with another model that makes a different kind of error, and average their predictions together. This is the principle behind model stacking, a type of ensemble learning.

I’ve been using the stacks package for creating these blended models:

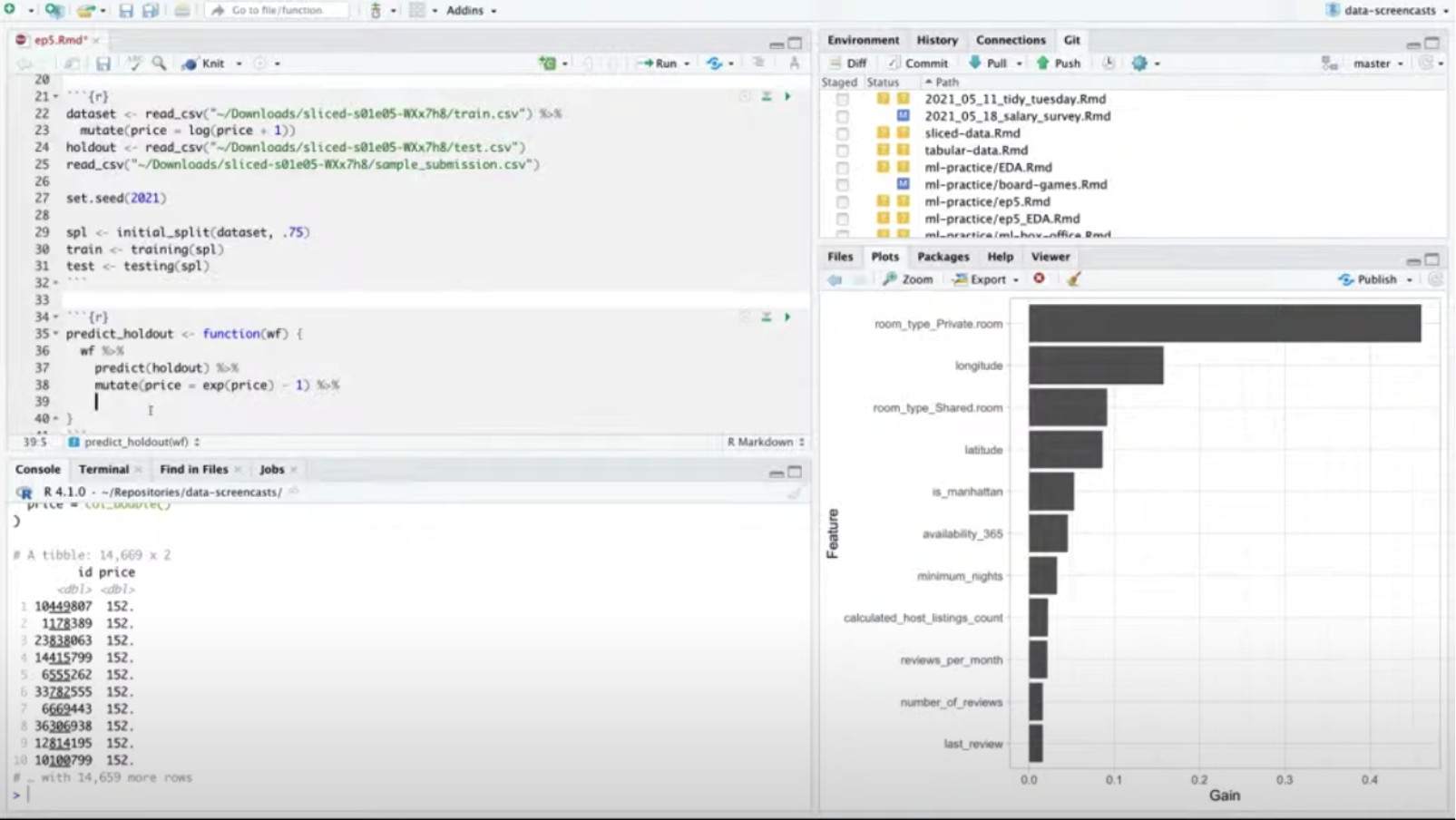

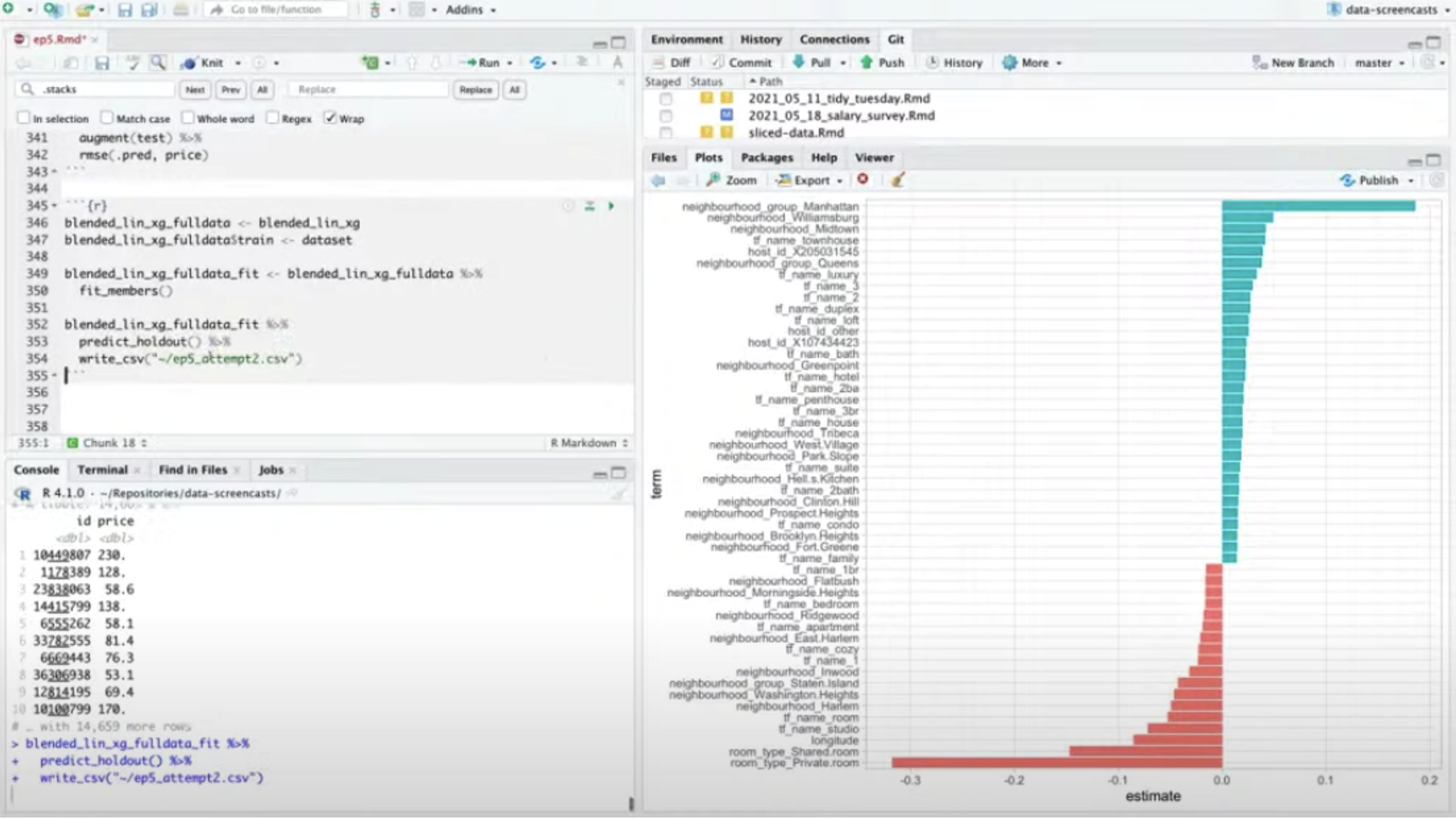

A perfect example was in the AirBnb pricing video. I was able to get to a strong model with xgboost based on numeric variables like latitude/longitude (very effective with trees!) and a few categorical variables.

But the data also included sparse categorical variables like neighborhood, and a text field (the apartment name) where tokens like “townhouse” or “studio” had a lot of predictive power

The stacks package puts this process within the tidymodels framework. Of all the tidymodels packages I’ve used, the stacks package is the one that’s most clearly in an early state. For starters, it’s overly opinionated about the way it combines models, always using a regularized linear model with bootstrapped cross validation. Partly because of that, it’s slow even when combining just two or three models. And I’ve found that it sometimes gives unhelpful errors when the inputs aren’t set up correctly, which suggests it needs some heavier “playtesting”.

Conclusion: I need to learn to meme

I learned a lot about tidymodels and machine learning in the process of competing. But my favorite part of the experience was that because it was hosted publicly on Kaggle, people watching the competition live could compete themselves (often outperforming the contestants!)

This meant we got to learn as a community, and joke around too.

This thread is for @kierisi and @kierisi only. If you're not @kierisi you can scroll past.

— Chelsea Parlett-Pelleriti (@ChelseaParlett) June 23, 2021

ARTISINAL SLICED MEMES FOR JESSE, a 🧵: pic.twitter.com/mYHR3bobGE

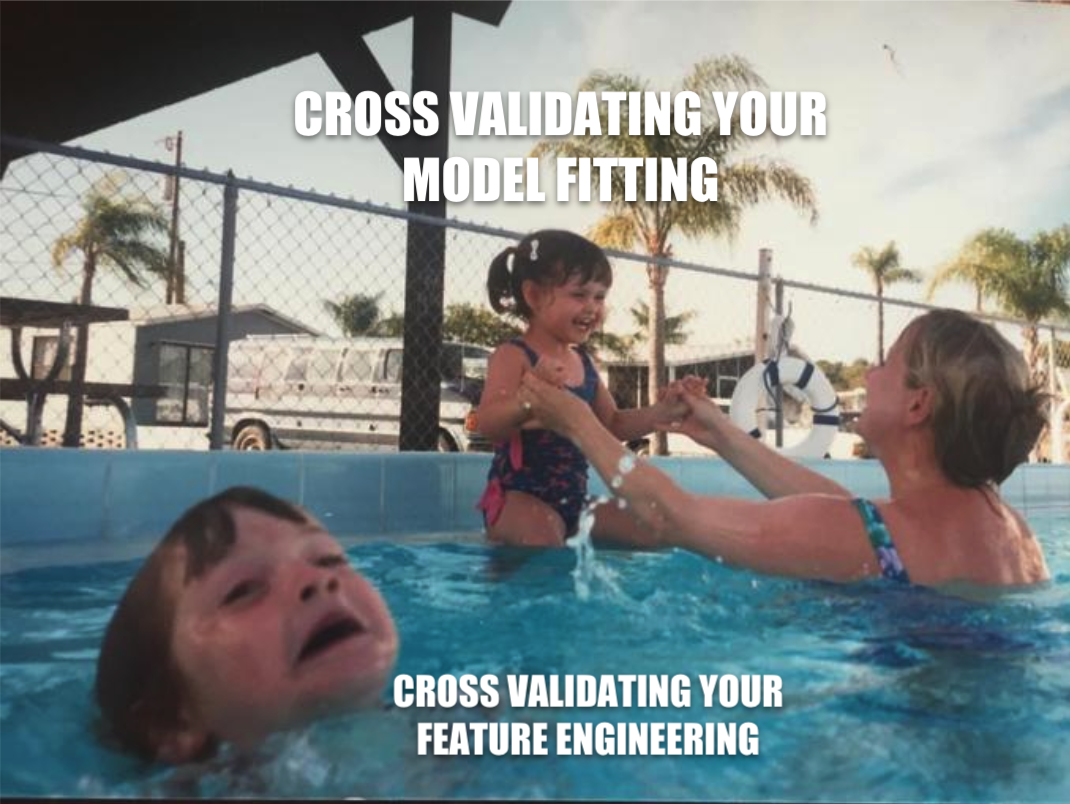

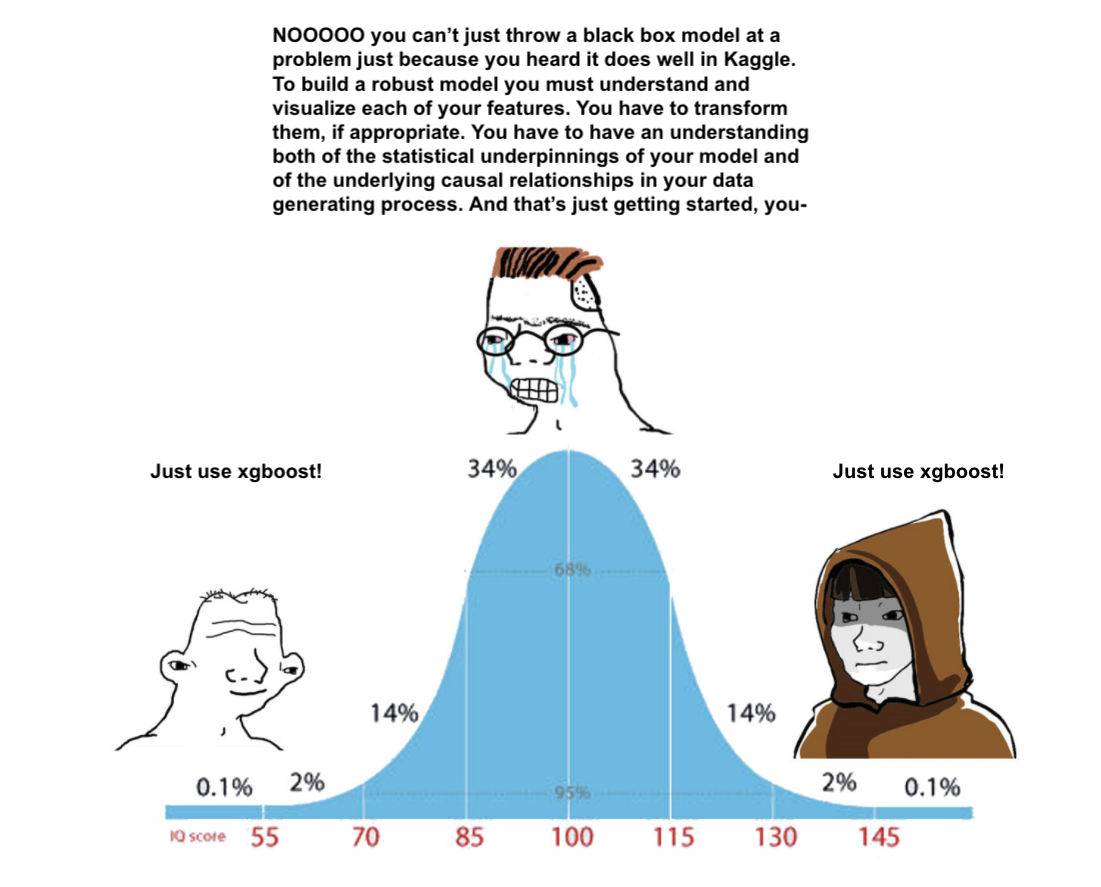

My competitor Jesse Mostipak came up with a brilliant schtick of showing memes on screen while her models were training:

This was at least one of the reasons she crushed me in the chat voting portion of our competition (and one of the reasons I’m trying out some memes in this post. Better late than never!)

No matter how far I make it in the playoffs, I’ll be joining in with some submissions every chance I get, and I’m honored to have had the chance to learn with everyone.

-

Thanks especially to my friend and colleague Julia Silge, who works on the tidymodels packages full time and helped talk through some of my thoughts and feedback on the packages. ↩

Re: Shiny, Tableau, and PowerBI: Better Business Intelligence [RStudio Blog - Latest Comments] 01:14 PM, Wednesday, 21 July 2021 05:20 PM, Wednesday, 21 July 2021

Indeed. R would be my first choice too, but I had to use Power Bi once,

and the Power Query M programming language it does its data

transformations is quite nice.